The hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is a critically endangered sea turtle belonging to the family Cheloniidae. It is the only extant species in its genus. The species has a worldwide distribution, with Atlantic and Pacific subspecies. E. imbricata imbricata is the Atlantic subspecies, while E. imbricata bissa is found in the Indo-Pacific region.[2]

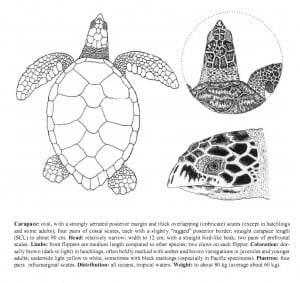

The hawksbill’s appearance is similar to that of other marine turtles. It has a generally flattened body shape, a protective carapace, and flipper-like arms, adapted for swimming in the open ocean. E. imbricata is easily distinguished from other sea turtles by its sharp, curving beak with prominent tomium, and the saw-like appearance of its shell margins. Hawksbill shells slightly change colors, depending on water temperature. While this turtle lives part of its life in the open ocean, it spends more time in shallow lagoons and coral reefs.

Human fishing practices threaten E. imbricata populations with extinction. The World Conservation Union. classifies the Hawksbill as critically endangered.[1] Hawksbill shells are the primary source of tortoise shell material, used for decorative purposes. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species outlaws the capture and trade of hawksbill sea turtles and products derived from them.

Ecology

Habitat

Adult hawksbill sea turtles are primarily found in tropical coral reefs. They are usually seen resting in caves and ledges in and around these reefs throughout the day. As a highly migratory species, they inhabit a wide range of habitats, from the open ocean to lagoons and even mangrove swamps in estuaries.[6][23] While little is known about the habitat preferences of early-life stage E. imbricata, like other sea turtles’ young, they are assumed to be completely pelagic, remaining at sea until they mature.[24]

Feeding

While they are omnivorous, sea sponges are the principal food of hawksbill sea turtles. Sponges constitute 70–95% of their diets in the Caribbean. However, like many spongivores, E. imbricata feed only on select species, ignoring many others. Caribbean hawksbill populations feed primarily on the ordersAstrophorida, Spirophorida, and Hadromerida in the class Demospongiae.[25] Select sponge species known to be fed on by these turtles include Geodia gibberosa.[4]

Aside from sponges, hawksbills feed on algae and cnidarians comb jellies and other jellyfish and sea anemones.[6] The hawksbill also feeds on the dangerous jellyfish-like hydrozoan, the Portuguese Man o’ War (Physalia physalis). Hawksbills close their unprotected eyes when they feed on these cnidarians. The Man o’ War’s stinging cells cannot penetrate the turtles’ armored heads.[4]

E. imbricata are highly resilient and resistant to their prey. Some of the sponges eaten by hawksbills, such as Aaptos aaptos, Chondrilla nucula, Tethya actinia, Spheciospongia vesparium, and Suberites domuncula, are highly (often lethally) toxic to other organisms. In addition, hawksbills choose sponge species that have a significant amount of siliceous spicules, such as Ancorina, Geodia, Ecionemia, and Placospongia.[25]

Life history

Life history

Not much is known about the life history of E. imbricata.[26] The life history of sea turtles can be divided into three phases, namely the pelagic phase running from hatching to about 20 cm, the benthic phase, when the immature turtles recruit to foraging areas and the reproductive phase when turtles reach sexual maturity.[27][28] The pelagic phase possibly lasts 1 to 4 years.[29][30] Hawksbills show a degree of fidelity after recruiting to the benthic phase,[31] however movement to other similar habitats is possible.[32]

Breeding

Hawksbills mate biannually in secluded lagoons off their nesting beaches in remote islands throughout their range. Mating season for Atlantic hawksbills usually spans April to November. Indian Ocean populations such as the Seychelles hawksbill population, mate from September to February.[8] After mating, females drag their heavy bodies high onto the beach during the night. They clear an area of debris and dig a nesting hole using their rear flippers. The female then lays a clutch of eggs and covers them with sand. Caribbean and Florida nests of E. imbricata normally contain around 140 eggs. After the hours-long process, the female then returns to the sea.[6][11]

The baby turtles, usually weighing less than 24 grams (0.85 oz) hatch at night after around two months. These newly emergent hatchlings are dark-colored, with heart-shaped carapaces measuring around 2.5 centimeters (0.98 in) long. They instinctively walk into the sea, attracted by the reflection of the moon on the water (possibly disrupted by light sources such as street lamps and lights). While they emerge under the cover of darkness, baby turtles that do not reach the water by daybreak are preyed upon by shorebirds, shore crabs, and other predators.[6]

Early life

The early life history of juvenile hawksbill sea turtles is unknown. Upon reaching the sea, the hatchlings are assumed to enter a pelagic life stage (like othermarine turtles) for an undetermined amount of time. While hawksbill sea turtle growth rates are not known, when E. imbricata juveniles reach around 35 centimeters (14 in) they switch from a pelagic life style to living on coral reefs.

Maturity

Hawksbills evidently reach maturity after thirty years.[11] They are believed to live from thirty to fifty years in the wild.[33] Like other sea turtles, hawksbills are solitary for most of their lives; they meet only to mate. They are highly migratory.[26] Because of their tough carapaces, adults’ only predators are sharks,estuarine crocodiles, octopuses, and some species of pelagic fish.[26]

A series of biotic and abiotic cues, such as individual genetics, foraging quantity and quality [34] or population density, may trigger the maturation of the reproductive organs and the production of gametes and thus determine sexual maturity. Like many reptiles, it is highly unlikely that all marine turtles of a same aggregation reach sexual maturity at the same size and thus age.[35] Age at maturity has been estimated between 10[36] and 25 years[37] for Caribbean hawksbills. Turtles nesting in the Indo-Pacific region may reach maturity at a minimum of 30 to 35 years.